Spain holds the largest Little bustard (Tetrax tetrax) population in Western Europe, (García de la Morena et al. 2006). However, this population suffered a 48% population reduction in 11 years (García de la Morena et al. 2018).

In the Ciudad Real province, which holds 60% of the Spanish Little bustard population, Cabodevilla et al. (2020) found a similar decline magnitude (46%), using the results of two national Little bustard surveys carried out in 2005 and 2016 (García de la Morena et al. 2006; García de la Morena et al. 2018).

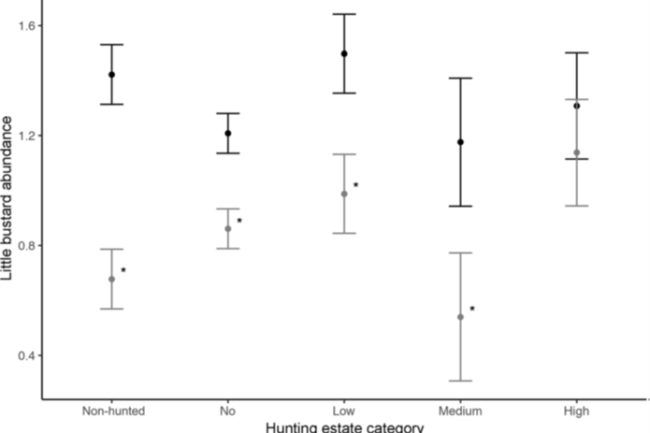

While the species declined in the province, it was found that this decline was not geographically homogeneous. Compared to similar Little bustard densities across different types of hunting areas in 2005, the species abundance decreased significantly in all categories except in hunting estates with high intensity of releases in 2016 (Cabodevilla et al., 2020).

Mean (± SE) abundance of breeding male Little bustards in each type of hunting estate and survey year (2005, black and 2016, grey). *P < 0.05. “Nonhunted” indicates non-hunting areas; “No” indicates hunting estates without releases; “Low”, “Medium” and “High” refer to hunting states with low, medium or high release intensity. Cabodevilla et al. (2020).

Predator Control

In such hunting estates, a range of management measures are frequently implemented to benefit game species which also benefit non-huntable species (Draycott et al. 2008; Estrada et al. 2015).

These management measures include legal predator control and the provision of habitats including game crops (crops planted specifically for game that are not harvested) which are probably the most beneficial for Little bustards (Estrada et al. 2015). These practices are significantly more frequent on hunting estates with high-intensity releasing (Arroyo et al. 2012).

As Little bustards were shown to be more abundant on hunting estates with high levels of Fox control than elsewhere (Estrada et al. 2015) and given that high intensity hunting estates were the only place in Ciudad Real where the species did not decrease between 2005 and 2016, the management carried out in these estates shows benefits to the species.

POLICY RELEVANCE

Nature Restoration Law: The European Commission has put forward a proposal for legally binding EU nature restoration targets in 2022. Restoring EU’s ecosystems will help to increase biodiversity, mitigate and adapt to climate change, and prevent and reduce the impacts of natural disasters. This Little Bustard story stands as an excellent example of how hunters are already contributing to delivering the EU’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. It accurately describes what can be accomplished for biodiversity and how to achieve those results.

Conclusion

More research is required to identify the specific management measures carried out in these hunting estates which are most useful to Little bustard conservation. This would be helpful to guide other estates and areas where the Little bustard is present. In the meantime, game crops and water provision as well as predator management carried out by hunters in these areas could be crucial measures for the conservation of the species.

RFEC

The Federación Española de Caza (RFEC) is the primary hunting association of Spain representing several regional Spanish hunting associations. Little Bustards prosper in several of these regions as RFEC advises the regions for strong conservation measures in favor of partridge and quail, which benefit all steppe birds. These measures include predator control, increasing the amount of food available to the Little Bustard, keeping the populations well maintained and in high density plus the increased rearing/release of other game species.

The measures were proposed as part of the eco-schemes in the common agricultural policy by the hunting sector (RFEC). In addition, the federation offers to lead a European project to test and evaluate different improvement and management methodologies for the recovery of the species, especially since it is a hunting region where the Little Bustard survives.

References

- Arroyo B, Delibes-Mateos M, Díaz-Fernández S, Viñuela J (2012). Hunting management in relation to profitability aims: red-legged partridge hunting in central Spain. Eur J Wildl Res 58:847–855

- Cabodevilla, X., Aebischer, N. J., Mougeot, F., Morales, M. B., & Arroyo, B. (2020). Are population changes of endangered little bustards associated with releases of red-legged partridges for hunting? A large-scale study from central Spain. European journal of wildlife research, 66(2), 1-10.

- Draycott RA, Hoodless AN, Sage RB (2008) Effects of pheasant management on vegetation and birds in lowland woodlands. J Appl Ecol 45:334–341

- Estrada A, Delibes-Mateos M, Caro J, Viñuela J, Díaz-Fernández S, Casas F, Arroyo B (2015) Does small-game management benefit steppe birds of conservation concern? A field study in central Spain. Anim Conserv 18:567–575

- García de la Morena EL, Bota G,Mañosa S, Morales MB (2018) El sisón común en España. II Censo Nacional (2016). SEO/BirdLife, Madrid.

- García de la Morena EL, Bota G, Ponjoan A, Morales MB (2006) El sisón común en España. I Censo Nacional (2005). SEO/BirdLife, Madrid.

Country: Spain

Species: Protected species, Invasive Alien species, Huntable species, Little Bustard

Species characteristics: Protected species, Invasive Alien species, Huntable species, Little Bustard

Type of actions: Management of habitats and wildlife, Nature education and awareness,

Leading partner: Federación Española de Caza

Other partners: Hunting organisations, Local governments